Throughout Punjab women embroider odhni(veils) or chaddar(wraps) ornamented with phulkari, literally ‘flower work’ and bagh, garden, a variation where the embroidery completely covers the support material. The fabric used is khaddar, a heavy cotton that is locally woven. The support fabric is most often an auspicious dark red, or more rarely an indigo blue or white reserved for elderly women, on which the embroidery is executed in untwisted floss silk called pat, sourced from Kashmir, Afghanistan, Bengal and dyed yellow, orange, burgundy, bright pink, purple, and blue in Amritsar. The Phulkari and Bagh are an integral part of the lives of women and ceremonies, especially those concerning birth, marriage, and death. When a girl child is born, the women of the family organise a feast, marking the beginning of the task of the child’s grandmother in creating the future bride’s trousseau, the most significant being chope-a reversible phulkari wrapped around the bride in the rituals before the marriage and the suber phulkari, composed of five eight petalled lotuses, worn by the bride when she walks around the sacred fire during the wedding. Phulkari only refers to sparingly embroidered flowers, whereas a large, intricately embroidered flower pattern is known as a Bagh.

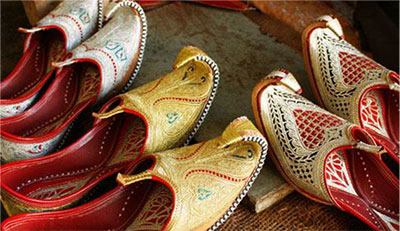

The ethnic footwear of Punjab, the jutti are hand-stitched, with tilla (silver and golden wire), embroidered uppers, and insoles. No nails are used in the construction of these jutti and no distinction is made between left and right foot. The density of embroidery varies from region to region within Malwa, where most production centers are located. Fazilka juttis feature chequered patterns, Muktsar juttis have multicolored tilla, Abohar juttis are light, embossed, cutwork, and beaded and the Muslim embroiders of malerkotla are famous for their fine and dense embroidery of shakarpara, sunhare, laharia, and jali motifs. Jutti making is a family occupation, the women embroider the shoe uppers while the men construct the shoes.

Panja Dhurries are intricately connected with the Punjabi concept of marriage that includes items of bedding; when the bride arrives at her in-law's house she brings with her a collection of auspicious eleven beddings, all embroidered and woven by her. Dhurries, traditionally worn by brides, are a symbol of their skill and family status. They are intricately woven with plump purple brinjal, massive red flowers, and Sanjhi Devi for auspiciousness. These dhurries are also woven for Gurdwaras by women using simple horizontal looms in a weft-faced plain weave, creating multiple forms and colours using wefts beaten into place with a panja, metal beater.

A common sight in rural Punjab, a region renowned for its cultural significance, is khes, a traditional handloom-woven fabric. Women in villages traditionally weave khes as part of their wedding trousseau. Khes is a thin cotton blanket cloth that is usually hand-woven from coarse cotton yarns and used for blankets and winter wraps. In Pakistan and northwest India, men also wear it as a form of clothing. The Sindh and Punjab region, specifically in the 19th and 20th centuries, is well-known for producing khes and other coarse cotton textiles.

In the early 19th century, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh brought Kashmir under his rule many Kashmiri carpet and shawl weavers migrated to Amritsar, an upcoming industrial town. This concentration of skilled craftsmen combined with the availability of fine quality wool from the neighboring hill states ensured the creation of exceptionally fine hand-knotted woollen carpets. In this technique, woollen yarn is knotted around individual threads of cotton warp. Of the patterns produced in the villages near Amritsar, the bokhra and mouri- geometrical patterns in black cream woven on a deep red, ivory, or green ground – are the main. The weavers use a colour-coded nakshak, a pattern drawn on a graph, while weaving new designs, depending on their memory to replicate the design, however today there are no naksha makers left in Amritsar; the companies commissioning the carpets provide their own graphs.

The district of Hoshiarpur produces dark sheesham furniture with painstakingly detailed dense foilage patterns that are both engraved and inlaid with acrylic, camel bone, and shell. The motifs are either of Persian origin or adaptations of the exquisite wood carving in havelis, mansions, of Hoshiarpur. The foliage pattern usually consisting of cypress trees is now being supplemented with figures and landscapes, the details of which are etched and coloured with natural ink. Acrylic is the primary material used in inlay after the ban on ivory.

Among the woodworking community of Hoshiarpur are the kharadi, lathe turners, who make turned wooden furniture ornamented with motifs etched on a lac coating usually applied in three layers-white, black, and red. After the lac is applied, a sharp metal stylus is used to etch motifs, thus revealing the underlying colours. Contemporary designs appear in white on a reddish-brown base. The craft of wood and lac turnery in Punjab has been influenced by various cultures and traditions, including Mughal and Persian craftsmanship. Skilled artisans in Punjab have honed their craft over generations, passing down their techniques and expertise to preserve this traditional art form.

Punjabis are known for their unique mud art, which involves which involves plastering of the house walls with mud and then decorating them with eye-catching designs. This art form, a thriving heritage in Punjab includes elaborate carvings and ornamentation on building exteriors, and these patterns frequently feature natural, folkloric, and religious themes, giving the buildings more personality and charm.

Chowkpurana, a type of temporary art created in Punjab, is drawn on the ground for decorative or ceremonial purposes. In Punjabi courtyards, chowk purana is occasionally drawn with flour and paint. The motifs stitched onto phulkaris are represented by the drawings. The flowers are coloured white, red, and yellow, while the branches and leaves are green. Such a chowk is called the phulkari chowk. While there are many varieties of chowk, they all begin with a flour-based square. Nonetheless, any pattern, including triangles or circles, can be created inside the square. Red sindoor (vermilion) is commonly used to draw dots.

Khunda or iron-tipped bamboo staves are carried by Punjabi farmers, the nomadic cattle herding Gujjars, and the Nihang warriors alike and are used both as a weapon of self-defence and as a walking stick. In addition, the khunda are also used as accessories by Bhangra dancers. The staves are made from whole bamboo poles that are cut to size in such a manner that the curved root of the bamboo is kept intact. The pole is then tinted a reddish-brown colour and ornamented with poker work, brass strips and brass nails, or kokas. The bottom portion is sharpened to a tip and wrapped in an iron sheet.

Basketry is a traditional handicraft in Punjab, primarily practiced by women. Initially used for household purposes, baskets have evolved into decorative items and showpieces. Basketry involves shaving thin straws of grass to create mats, rugs, carpets, curtains, and hand fans, known as Peshawari pakkhe or kunda ladar pakkhi. Other products include tokris, chaj, changair, tiffin baskets, waste paper baskets, and oval-shaped containers. The abundance of raw materials, such as bamboo, cane, reeds, grasses, munj, palm leaf, date leaf, and cornhusks, makes basketry a popular household craft. The straw, commonly called sarkanda, is widely used in Punjab for basketry.

Jandiala Guru, a crafts village in Punjab, is known for its traditional brass and copper utensil making, a practice that has been recognized as an Intangible Cultural Heritage by the UNSECO. The Thathera community has a rich history dating back over 200 years, with the craftsmen colony established during Maharaja Ranjit Singh's reign who encouraged skilled metal workers from Kashmir, to settle in his kingdom. The village has become a hub for producing brass and copper utensils, a traditional skill and knowledge system that is still practiced today. The products made by the Thatheras are considered beneficial for health.