In winters, the main stalk of the sarkanda plant dries up and the grass is harvested and ingeniously transformed into a variety of products. The thicker parts are used to make stools known as moodha, while the outer skin is used as thatch. The tuli, top half, is made into baskets, and the leafy covering moonj, is beaten into fibre and twisted into jeverdi, rope, which is used to web local furniture such as charpai and peeda and moodha (stools).

The moodha is a low circular stool made by aligning sarkanda in a criss-cross construction that is tied along the spine. The local women make further use of this material by coiling baskets and making traditional products like shallow baskets called changeri and the larger boiya, bread baskets, that may or may not have a lid. These are often bound with gota, coloured threads, date palm and patera leaves. A variation of the changeri is the sundhada; it is bound with a naulai or wheat stocks. The indhi, used as supportive base for carrying water pots on the head is also made.

The craft of making palm leaf baskets was introduced to Haryana by women of the Multani-speaking Audh community who had migrated from Pakistan during Partition and taken up this craft as a means of supplementing their meager earnings. Traditionally the raw materials were the locally grown date palm: phoos, a wild grass; and pula, thin leaves of the sarkanda plant, these were made into coiled baskets intended for domestic use by the womenfolk of the household. The products include a range of round-bottomed, cylindrical, and shallow baskets with and without lids. The leaves are also plaited into strips and formed into bags and mats. The dry palm leaves, some of which are dyed so as to achieve a coloured pattern, are wound around a bunch of phoos or pula and sewn in place by threading the leaf through the lower coil; a big blunt needle is utilised to push the leaf through.

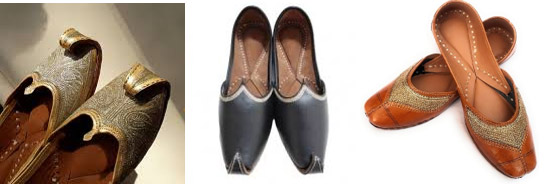

Hissar and Rewari are the two most important clusters where ethnic footwear is made in Haryana. At Rewari and Jhajjar, jutti with curled toes and industrial zari, gold thread embroidered uppers are made; of these, the black leather jutti embroidered with golden wire were worn only by the wealthy and influential while thin soled jutti with an elongated curled toe are reserved for use on special occasions. The cobblers of Hissar make robust and highly durable unadorned slip-ons, known locally as the desi jutti, for farmers. The one-pieced uppers of thick hide are reinforced at the heel with appliqué and the sole is made from several layers of buffalo hide that are stitched with thick cotton thread. The munde (round toed) or ghuni (pointed toed) are worn by men and women.

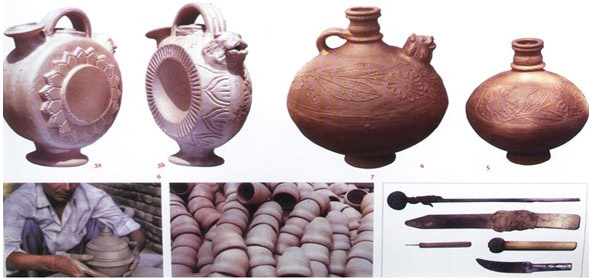

The Kumbhars of Jhajjar are skilled potters who create slim-necked pitchers called surahi, made from a combination of thrown and moulded parts. The process involves entire families, with women and children preparing clay, while men create the wheel-thrown surahi necks. Clay is rolled and stretched over an upturned pot, then pressed into hemispherical terracotta dies engraved with patterns. The clay shrinks, leaving the surface, and the spouts, necks, and handles are attached by women. Surahis are then dipped in a slip made of banni and sunaihri, red and yellow clays, and dried before being fired in mud kilns. Surahi, an Islamic form of pottery, likely originated from local craftsmen in Delhi during Mughal times. The earliest surahi were unembellished and fully thrown, while the current form is an indigenous adaptation. Pots like diya, golak, and kulhar are also formed, serving as water pots for rituals and birth and death ceremonies.

Traditional kitchen utensils in Haryana, made by dry pressing and cold forging sheet brass, are part of marriage customs. Pots used to collect and store water are crucial in the area. In Rewari, circular brass ingots are sand-cast by specialised craftsmen and sent to small industries for sheet rolling. The joints, neck, and mouth are gas welded, and the products are hand polished with mud, tamarind, and sandpapered. The utensils' perfectly aligned symmetry is a testament to the craftsmen's practice.

Mangali village in Haryana, India, produces wooden prayer beads that have been crafted for over sixty years. These beads, made from woods like keekar, sheesham, and teak, are strung together with a cord or thread. The villagers, regardless of caste or community, craft these beads in their free time, selling them to middlemen from other states. The beads are sold in various Indian and foreign cities, including Delhi, Kolkata, Varanasi, Haridwar, Jaipur, Mathura, Bodh Gaya, Nashik, and southern states, as well as to Arabian countries. The beads hold religious and spiritual significance in Hinduism, Sikhism, and Islam. The Hindu 'Japmala' contains 108 beads, while Sikhs use them for reciting Guru Granth Sahib verses. The Muslim rosary has a slightly lower number of beads, referred to as Tasbih.

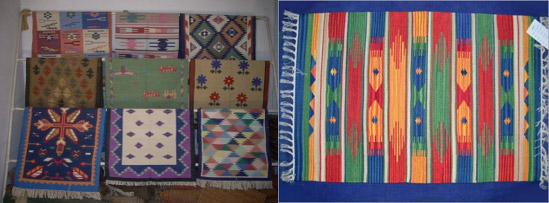

The Durrie weaving craft, originating from the local dialect, is a skillful and vibrant art form that is primarily woven by women. The craft gets its name from a metallic claw-like tool called punja in the local dialect, used to beat and set the filling threads. Durries are woven into various shapes and designs, such as stripes, check boards, squares, and pictures of birds, animals, human figures, and plants. They are used on floors, beds, and diwans in Haryana. However, the Durrie weaving tradition is diminishing due to factors such as lack of demand, poor marketing, and lack of incentives for creative expression. Weaving durries is a tradition that is limited to women. At a very young age, a girl is taught to weave by older women in the home, such as her mother, grandmother, paternal aunt, or sister.

Chowkpurana is folk art practised in Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh. It refers to decorating the floor with various designs using flour and rice and the walls using designs specific to the region. In Harayana artists plaster the mud walls with cow-dung which is then whitewashed. Lines are then drawn which create symbolic paintings representing "profit, fortune, and prosperity"

Haryana's sculptural history dates back to the Harappan and Indus Valley civilisations, with numerous ceramic pieces, seals, and terracotta figurines discovered at excavation sites. These artefacts showcase the creative sensibility of the period, with human and animal shapes. During the medieval era, Haryana saw the rise of spectacular temples and forts decorated with elaborate sculptures, combining Indo-Islamic elements. The intricate carvings on mosques and tombs showcase the artisans' skill and craftsmanship. The Adalaj ki Vav in Faridabad is an example of this artistic syncretism. Haryana's rich folk and tribal communities continue the state's sculpture legacy, creating statues and figurines from clay, metal, and wood that represent their way of life and cultural ethos.