The Kutch work or Kachchhi embroidery derives its name from its origin place - the Kutch region of Gujarat. It is characterised by its use of bright colours; mirror beads and embroidery that decorate the entire fabric on which it is based. Usually crafted on cotton or silk fabric, Kutch work embroidery is done with silk or woollen thread using fine stitches to create detailed patterns. Designs are inspired by architectural and human motifs; Persian and Mughal art. The colours used are mainly green, indigo, deep red, black, yellow and ivory. History traces the origin of Kutch embroidery back to ‘mochis’, the community of shoemakers. The embroidery is also believed to have been brought about by Kathi cattle breeders.

Rabari embroidery is named after the Rabari community, nomadic cattle raisers from Rajasthan settled in the Kutch region in Gujarat, India. This embroidery uses mirror chain stitches in different sizes and shapes. They use a wood embroidery hoop, a special needle and woollen threads (sutar). Rabari embroidery can be seen in items like Torans, scarves, shawls, backless blouses (kanchali), skirts (Paheranu and Ghagharo), woollen veils (Ludi), bridal dresses, handbags, bed covers, and camel decorations. The designs are inspired by myths and desert life.

Zari stitching is an ancient Indian craft that has been highly valued for generations. The origins of Zari work can be traced back to the Mughal era in India, around the 16th century. Influenced by Persian craftsmanship, Zari found its way into the royal courts, adorning garments worn by the nobility. This intricate form of needlework uses metallic threads, often gold and silver, to create elaborate patterns on traditional garments like saris and lehengas. The term "Zari" comes from the Persian word for "gold," highlighting the shimmering threads used. Zari embroidery holds cultural significance, often valued as a symbol of prestige and is associated with special occasions and celebrations. The rich history and meticulous craftsmanship involved in Zari work make it a fascinating aspect of India's textile heritage.

Patola is a double ikat woven sari, usually made from silk. The word patola is the plural form; the singular is patolu. They are very expensive, once worn only by those belonging to royal and aristocratic families. It is generally worn on auspicious and important occasions. Velvet patola styles are also made in Surat. Patola-weaving is a closely guarded family tradition. Three families in Patan weave these highly prized double ikat saris. It is said that this technique is taught to only the sons of the family. It can take six months to one year to make one sari due to the long process of dying each strand separately before weaving them together. Patola was woven in Surat, Ahmedabad and Patan.

This 700-year-old weaving craft is native to the Dangashiya community of Surendranagar, Gujarat. The community consists of weavers and shepherds. The weavers make the blankets out of sheep and goat wool for the shepherds to wear. Tangaliya is a labour-intensive and tedious process. Contrasting coloured threads are twisted onto a group of four to five threads of warp, creating dana or beadwork. The geometric motifs give the impression of intricate weaving, though they are extremely sturdy in their shell life. Together, they create beautiful patterns. Today, these textiles are used to make dupattas, dress material, bedsheets and pillow covers.

Bhujodi weaving, a well-known craft from the Kutch region of Gujarat derives its name from “Bhujodi”; one of the oldest and biggest artisan villages. It is home to the Vankars (weavers). The speciality of the weave is how simple geometric motifs is used to create a piece of art. For years, the weavers of Bhujodi have created a harmonious barter system between themselves and the Rabari clan (cattle herders). The Vankars began to experiment with cotton (Kala cotton) that was sourced locally and naturally grown. However, the woven fabric served limited purposes to the weavers as it was extremely thick, but it allowed them to play around with colourful designs. The Bhujodi weave uses geometric motifs such as triangles, stripes, diamonds, star shapes and chevrons. Most of their designs are created with linear patterns filled with motifs that run throughout the fabric.

The tie-dye textile technique of Bandhani or Bandhej or Bandhni has been in practice in the state of Gujarat as far back as the 12th century. Visual references to Bandhani have also been found in the cave paintings of Ajanta and Bagh. Creating Bandhani patterns involves tying knots at varied lengths and shapes in a textile before dyeing. This results in the creation of unique designs and patterns. The Ahmedabad city of Gujarat is famous for Bandhani designs. Today, colourful Bandhani are being sold all over India and their demand has increased. Bandhani patterns incorporate a diverse array of motifs, ranging from geometrical patterns, and flowers, to richly woven folklores and cultural symbols specific to the region.

The term "Rogan" comes from Persian, meaning oil or varnish. This technique was introduced during the Mughal era and arrived in Kutch about 400 years ago. Despite its Persian origins, Rogan art developed uniquely in India and doesn't resemble crafts from other parts of the world. Remarkably, Rogan art is created entirely by hand. Artists create a design on one side of the fabric and then transfer a mirror image to the other side, achieving beautiful symmetry. An interesting aspect of this art is that the metal pin used to guide the thick paint never touches the cloth. This art is practised by the Khatri community in the small village of Nirona in Kutch. The paint comes in yellow, red, green, white, orange, and black. Traditionally, Rogan art decorated bridal clothes, scarves, and skirts.

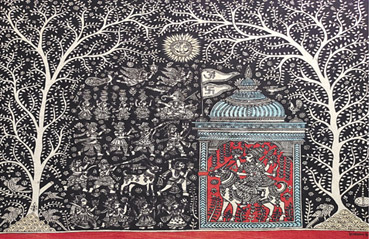

The original creators of Mata ni Pacchedi were the Devi Pujak who lived along the edges of the Sabarmati River in Gujarat. Translating to ‘behind the Mother Goddess”, these textiles are sacred, wall art pieces used as a backdrop for shrines. The original style only involved using two colours - black and red, made out of natural dyes. The illustrations on the cloth consist of a central deity surrounded by designs showing nature, light, animals, and artistic creations all worshipping the Goddess. The designs are made using hand block prints and freehand painting.

In terms of origin, Ajrakh is a form of block-printing found in the Sindh region of present-day India and Pakistan. It is believed to have existed as far back as 3000 BCE. This delicate block printing technique, which found its way to the Kutch region, is a blend of culture and tradition. Ajrakh’s flexibility comes to the forefront with its application on various textiles, such as sarees, dupattas, and basic cloth. The naming of Ajrakh originates from ‘azrak’, meaning indigo, with indigo being the most commonly used dye in this textile art. Traditionally, Ajrakh prints have consisted of three colours: blue, symbolising the sky; red, representing the land and fire; and white, signifying the stars.

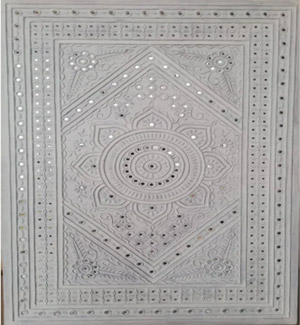

Lippan Kaam is a traditional mud art from the sandy and marshy areas of Kutch. It is used to decorate walls, doorways, and ceilings of huts. In the Rann of Kutch, you can find mud houses called bhungas, decorated with beautiful mirrors and clay designs. This art isn't just for looks; the decorated walls help insulate homes from the intense summer heat. The designs, often featuring shapes and motifs like elephants, camels, and village women, vary by community. The Rabari and Ahir communities, known for their nomadic lifestyles, incorporated mirrors extensively into these mud designs. Lippan art is full of meaningful motifs. For example, circles represent life's cycle and the universe's eternity, while peacock designs symbolise prosperity and good fortune.

Textile workers in Ahmedabad use papier mache techniques to create colourfully painted and elaborately designed figures of deities, toys and various other artefacts. It is widely used in traditional Indian folk art and has found a place for itself in the home decor market. Ahmedabad is a popular art form practised in Gujarat and you’ll see people making lampshades, bowls, vases, jewellery and furniture.

The potters' village of Gundiyali in Kutch, Gujarat is well known for its beautiful and unique terracotta craft of India. The painted pottery of this village is distinct for its deep red shade, smooth finish and the painting work done on the surface of the pottery. Khavda pottery, originating from the Kutch region of India, is an ancient art form with over 5000 years of history. This unique craft uses local clay and natural paints to create various items such as pots, kitchen utensils, decorative pieces, and toys. The designs are inspired by nature and feature intricate, dotted patterns similar to those found in Indus Valley artefacts. Khavda pottery's distinctiveness lies in its handmade process and eco-friendly materials.

Gujarat has been a major centre for woodcarving in India since at least the 15th century. Timber was commonly used in the past to provide strength and stability to multi-storeyed houses. Even today, many people in some of Gujarat's old, well-preserved towns live in wooden houses. The Vadha community, a semi-nomadic group in northern Kutch, is known for its skillful lacquered woodwork. Their techniques and motifs are shared with regions like Rajasthan and Sindh. The vibrant woodwork created by the Vadha community include a variety of items such as kitchen utensils, containers, door frames, and cradles. This rich tradition of woodcarving reflects Gujarat's cultural heritage and craftsmanship.